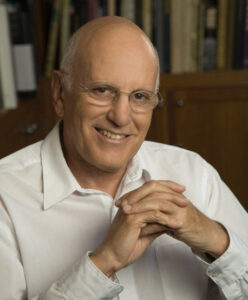

An Interview with David Richo, PhD, MFT:

|

David Richo, PhD, MFT is a psychotherapist, writer, teacher, and workshop leader whose work combines Jungian, Buddhist, and mythic perspectives. He’s the author of numerous books on psychological and spiritual growth, including How to Be an Adult in Relationships and The Five Things We Cannot Change. He lives in Santa Barbara and San Francisco, California.

We talk here about the five elements that form the basis of trusting relationships and spiritual maturity, achieving “good enough, most of the time”, repeating what’s incomplete, staying too long or leaving too soon, examining our reactions to triggers, saying yes to the givens of human existence, misusing spirituality, and forgoing retaliation. |

The following resources were mentioned in the interview:

- When the Past is Present

- The Five Things We Cannot Change

- Triggers

- How to Be an Adult in Faith and Spirituality

- How to Be an Adult in Relationships

- David’s Website

Transcript

Ryan: Okay. Well, David, thanks for joining me today.

David: Thanks for inviting me.

Ryan: You bet. So why don’t we just start – I will have on my website just give a little bit of a background about who you are – but can you, in your own words, tell us a little bit about you?

David: I’m a psychotherapist and writer, and I’m here in Santa Barbara, California. And I attempt in my work to integrate the psychological and the spiritual and also have a great interest in poetry. So I try to bring that into what I do also.

Ryan: How are you splitting your time these days?

David: Right now I’m in Santa Barbara for a while because of the COVID situation, but I usually live part of the year in the Bay Area.

Ryan: Actually, what I was meaning to ask was in terms of how much psychotherapy you do, how much time you spend writing – are you focusing on some more than others?

David: It’s probably mostly psychotherapy and then I do my writing at least a couple of hours a day. It’s part of my spiritual practice to share whatever I know or whatever I think is going to be useful to others.

Ryan: And I wanted to ask just about your background and where you’ve gathered inspiration along the way. I know that’s a big question, but in terms of your spiritual practice and how that’s evolved over time, and also how it began.

David: It began religiously, because I was brought up in the Catholic faith and then I found Buddhism in the early 1970s, and so I mainly had a Buddhist practice, but now I’m kind of combining some Christian and Buddhist ways of practicing. Practice meaning: where meditation might take us and how we show our spiritual awareness in our daily choices and actions. That’s certainly a challenge.

Ryan: Absolutely. And if we were to stretch back even further, in terms of some of your early influences, what would you say motivated you to move in the direction of spirituality psychotherapy as a way of life?

David: I think my interest in psychotherapy was recognizing how messed up I was myself. And I thought by going into that topic, I would get healthier. And of course, that doesn’t really work. So I did some therapy on my own. And then regarding spirituality, I just always had an interest and, actually, enthusiasm and excitement about the mysterious hidden reality behind what we see. And I still don’t know what that is, but I’m just very drawn to more than what the eye can see, that we are more than what’s on our driver’s license.

Ryan: Right. Well, you mentioned some combination of Buddhist practice, Christian practices, and of course, those have been the subjects of a few of your books and also those themes find their way into almost all of your books, it seems. I wanted to ask about some of the other themes that I’ve noticed in several books that I’ve read of yours. And one is these five A’s. So you emphasize these five ways of being that form the basis of loving and supportive relationships. And that can be relationships with ourselves, or in our personal relationships. So can you tell us about these five and maybe just elaborate on those a bit more?

David: Sure. Well, we’re born into a world with many needs, and I identified five specific ones. They all happen to start with the letter ‘A’. So I call them the five A’s. And the first one is attention or attentiveness, because we came into the world requiring 24-7 attention and we also came in nonverbal. So we needed somebody – that is our caregiver or caregivers – to know when we needed to be fed, when we needed to be changed, when we needed to be held. And so attention from others toward us was one of our needs. And ‘needs’ is a requirement for development. So in order to grow, or even to survive, somebody had to pay attention to us.

Likewise, we now know that the brain isn’t fully formed at birth and is helped in this formation by physical affection – hugging, holding, and that is the second need. Everyone needs to be held and cherished and played with. And when that happens, we develop as humans. Then we started to show personality characteristics and our need was to be accepted as we are – introvert or extrovert – whatever form our personality takes. And then we needed to be cherished and valued. So that’s appreciation. And then finally, when it comes time for us not to be so dependent on our caregivers, we needed to be allowed freedom. Obviously, all humans have a right to freedom. It isn’t about giving us freedom; it’s about permitting us to exercise our freedom. So that’s allowing. And it began when we crawled across the floor instead of needing to be carried across. And then went to leaving home to go to school, leaving home to go to college, or to whatever our adult life was going to look like.

And those are the five A’s: attention, affection, acceptance, appreciation and allowing. And then it turns out that those are the exact same five A’s that we need in our adult relationships. So I want to be with somebody who gives me those, and I give those back to the other. And when two people or more share these five A’s, that’s what I consider to be intimacy. Those are a way to build trust.

Ryan: Ways of building trust, and also the ingredients for intimacy.

David: Yes.

Ryan: Right. Now, of course, in our early family experiences, each of us has gotten these five A’s in varying degrees. Sometimes a lot of it is available, and sometimes, for all sorts of reasons, it’s lacking. And so I was hoping you could talk a little bit about as we launch, and as we move into the world and we start trying to build adult relationships, close relationships, it seems to me that part of what you’re saying is that we’re really looking for those five A’s throughout our adulthood and trying to meet those needs in ways that maybe they weren’t entirely met in those early years.

David: Yes. We keep looking for what we instinctively realize was supposed to happen. Like part of being born as a mammal is being cared for by parents. And when it was lacking, we would be seeking it ever after. And when it was there and when it did happen, we would no longer need it in an impulsive way where we’re constantly seeking it and can’t ever be satisfied. And I explained this in my book, When the Past is Present – the title says it all – that what happened to you in the past is influencing what’s happening in the present, and it’s all based on the needs and whether they were fulfilled. When they were fulfilled, then you have received what you needed. And ever after, you’ve just looked for a moderate dose from other adults of the five A’s. And when they weren’t – when one or more of them was not forthcoming, there’s a hole inside, and you’re always trying to fill it.

But unfortunately, not receiving need fulfillment at the beginning also means not receiving the capacity for satisfaction. So it’s a terrible situation to be in because, one, you didn’t get what you needed. And then, two, when what you need does come along, you don’t have what it takes to be satisfied with a reasonable, moderate amount. You have kind of a bottomless pit inside and you keep wanting to fill it.

Healthy people will not want to do that with you. They won’t like being with somebody who’s clinging and needy. So you wind up suffering again, because you’re in a relationship that isn’t really able to work. But we shouldn’t be despairing about any of this because the state-of-the-art way of doing therapy helps us to grieve what was missing in the past, to let go of blaming our parents and to launch ourselves and give ourselves these five A’s. That’s called self-parenting. And that’s what helps us heal the wounds of the past and helps us fulfill ourselves.

And then we also get the capacity to be satisfied with less which is all other humans offer. Nobody offers 24-7 perfect love. Everybody offers limited versions. Healthy people have realized that one of the givens of life is that there will be limitations in all human interactions and let that be okay.

Ryan: And you’re suggesting that as somebody starts to feel more fulfilled through self-parenting, through an understanding of that given, that not everyone is going to be able to provide that perfectly all the time, relationships tend to go better?

David: Yes, and also you would attract a healthier candidate for a relationship because it would be somebody else who also has accepted the given of limitation and is not coming from the bottomless pit.

Ryan: Yeah. Perfectly legitimate to be pursuing these five A’s throughout our lives – it’s a necessity even. We just want to be doing that in a way that’s realistic.

David: Yes. The way I would put it is “good enough, most of the time.” I would make that my healthy motto. The five A’s are coming to me in a good enough way most of the time. And that in itself is a very adult statement because it has acknowledged the limitations. It’s not going to be perfect; it’s going to be good enough. It’s not going to be all the time. It’s going to be most of the time. Even some of the time could be okay, but not not at all.

Ryan: Right. So you’re describing a scenario in which somebody is actually pursuing those needs, maybe out of a place of desperation, or they have an exaggerated sense of needing those five A’s, that something was missing. I’m also thinking about situations in which we end up in relationships that end up being re-wounding. So the five A’s aren’t even present. Maybe the person isn’t even aware that those are essential needs. And instead, the relationship is volatile or it’s chaotic in some way, it’s hurtful. So the opposite of these things are happening. How do you understand that? Why might we, even though we are looking for these five A’s in our adulthood, especially because they were missing in our early life, end up nonetheless in situations that just repeat some of the original experiences of wounding?

David: Well, the part of us that wants to repeat is stronger than the part that wants to complete. That’s just human nature, what Freud called the repetition compulsion. Also, when something is incomplete, it leads to repeating. Or another way of saying it is, you’re repeating it because it’s incomplete. And these aren’t just words; this is a look into human nature.

Instead of trying to complete something, we simply repeat it believing – and this is a healthy thing about us – that maybe if we repeat the whole scenario with someone new, that person will get us through it. Instead of doing our own personal work to complete our childhood scenario, we’re hoping that somebody else will simply cancel that need by giving us what we want. But of course, we meet up with people who not only repeat the original scenario, but they also repeat the incompleteness of it.

Ryan: I often have the sense that we’re also just more comfortable in the familiar, and that finding ourselves in a situation that would actually be ultimately fulfilling for us, in terms of the five A’s, is just too unfamiliar, it’s too much for the system to enter into comfortably.

David: Yes. I agree.

Ryan: So you’ve been in practice for a long time and one of the things I wanted to ask was if there were particular ways in which people are showing up, or particular issues that you’ve seen over time as being most common?

David: Okay. And last year was my 50th year as a therapist, and I did ask myself the question, “what was the most common topic? What was the most common problem that I encountered among the thousands of clients?” And the answer was “staying too long in what doesn’t work.” And that is the topic of the book I’m working on now, which is going to be about why we stay too long in what doesn’t work and why we also sometimes leave too soon something that could work. And both of these are ultimately about a much more mysterious topic, which is timing. Like, what makes us ready on Monday, but not on Sunday, and then it’s too late on Tuesday?

So I’m very fascinated with that mysterious suddenness with which we might have an awakening and make a move or a change. And people try to convince us to do the right thing or make a change, and we say “yeah, you’re right, I really should,” but then we don’t. But then one morning, we wake up and we say, “today’s the day.” To me, that’s very interesting and a very exciting topic to explore. So I’m enjoying that, enjoying looking into that, and I don’t have any answer to it. As I say, it’s more of a mystery but it’s certainly worth exploring. And of course, we’ve all done this. We’ve all stayed too long. We’ve all left too soon. And we also all have had the experience of timing kicking in, as Shakespeare says, “the readiness is all.” In other words, the readiness is what really matters. Are you ready to make whatever the move is?

Ryan: Right. I’ve always had the sense in your writings that you’ve been not willing to state definitively about things being this way or that way, but having an appreciation for the mystery of some of these themes that you write about. But could you give us a little bit of a preview of some of what you’re starting to unpack as you do that exploring?

David: You mean regarding why we stay too long in what doesn’t work, or…?

Ryan: Staying too long or leaving too soon.

David: What I’m coming up with so far is: we stay too long because we’ve been taught that enduring pain is the purpose of life rather than being happy. And we can see how we might have been taught that from our religious background, and also from observing our own parents. If they were in unhappy relationships, we would think to ourselves, “well, I guess that’s the way it works here. You just endure and that’s success, rather than up and go after trying whatever you can to get something to work.” And when you can reasonably say, “I put all the energy into it that I can and I have used the state-of-the-art methods of therapy to try to get this relationship to work and it still doesn’t,” then it would be the moving on time. And that’s going to be hard to do if you don’t believe that it’s okay to be happy.

Ryan: Right. Alternatively, you might have a belief that says, “if I can hang in there and endure, that means that I’m strong,” or something like that.

David: I was just thinking of a statement that St. Bernadette shared. Of course, she’s the one who saw Our Lady of Lourdes in a vision. And when she told her friends and villagers and priests about the visions, they didn’t believe her and they kept telling her that she was delusional. And at one point, she said to the Virgin Mary, “since I’ve met you, I’ve had nothing but trouble.” And our lady answered – and this is the point I’m making – “remember, I never promised you happiness in this life, only in the next.” So that’s the statement that we were brought up with. You just endure suffering in this life and then you will have an eternity of happiness. And nowadays, we have doubts about that kind of a statement because it keeps you tied to what doesn’t work and it keeps the nuclear family around the hearth, when actually, you would be healthier and happier if you were branching out as individuals.

Ryan: Even with that understanding, it can still be terribly difficult to actually make that decision.

David: Yes, because the conditioning that we’ve received was not already oriented toward how to make things work for yourself, while also being loving toward others. It was about how do you put up with whatever the situation is once you are in it. How do you stay put in what doesn’t work since you’ve promised that you would? And of course, we shouldn’t be held to promises that we made before we had the full picture of what the situation would really be about.

Ryan: Right.

David: So that’s the problem with that kind of a vow.

Ryan: I’ve really noticed this in my own counseling practice, as well, that there’s a way in which folks have been able to articulate very clearly, “this isn’t working for me,” and they can walk through all of the ways in which that’s true. But what they’re really seeking the support around is “how do I actually make that decision and how do I trust myself to get through all of the tumult that would likely follow, skillfully.” People are often very nervous about that.

David: Yea. And fortunately, now we do have state-of-the-art ways, thanks to the self-help movement, to make it easier to navigate through what you’ve just described.

Ryan: What are some examples? How do you mean?

David: For instance, if something isn’t working, you can go to therapy and try to get it to work, try to become more skillful in how you are together in the relationship. And then if it does get to the point at which you see that it can’t really work and it’s only being hurtful to both of us, then there’s a way to separate with love instead of retaliation. And there’s a way to get some sense of closure, not by having the other person acknowledge your pain, but experiencing your pain as grief about what didn’t work. Letting yourself feel sad that it didn’t work, angry at what all has happened and afraid of the future. And you can learn ways to have all those feelings without being destabilized by them. In my book called Triggers, I give some ideas about how to do that. But yeah, it’s really about taking advantage of all those skillful means that are being offered to us both in psychology and spirituality.

Ryan: Yeah. It sounds like you’re saying historically and culturally, perhaps, those practices were a little more difficult to access or there might have been stigma or taboo, or something like this?

David: Yes.

Ryan: Right. So you mentioned just a moment ago your book Triggers, and maybe we could transition into some of the themes that you described there. So in your book, you say that triggers can be very difficult to shake off. Each of us knows this from personal experience that triggers are triggers because of their persistence and the ways in which they can just seize us. And I wanted to ask how you understand the difficulty of actually freeing ourselves from some of these triggers, whatever that might be.

David: I recommend in the book that you trace the origin of the trigger to something that has to do with yourself. “Why am I reacting so strongly to being snubbed by this person?” for instance. So the snubbing is the trigger, and the reaction is sadness or anger or even the need to get back at the person. But if we looked into it from a personal point of view, asking ourselves, “what is it in me that gets so upset by any kind of rejection, especially since rejection is one of the givens of life? There will be people who will reject me. There will be people who accept me.” And when you go in that direction, you find out more about yourself and then you can do whatever work goes with what you found out. So for instance, you could find out that that’s exactly what happened in childhood.

Ryan: Rejection.

David: So it’s another area of grief about how you were rejected. Or it could be about how you were rejected in other relationships, or how you were picked on in school, or whatever happened to you that, shall we say, stuck in you as a personal peeve. And here comes somebody who pushed exactly that button. And so I’m actually reacting to a whole lifetime of rejections rather than just to this one. So that accounts for why it’s such a big reaction. It doesn’t seem to fit with the original stimulus that happened yesterday. This is connected to all the yesterdays. And since I never grieved all those rejections, they piggyback on to this one, and they present their bill. So a person who really wants to work on himself or herself or themselves would get this and would say, “oh, I see I have some personal work to do,” rather than blaming or getting back at the one who snubbed them. In that sense, then the one who snubbed you, has actually done you a favor.

Ryan: They’ve presented an invitation of sorts to actually go towards the work that we need to do.

David: Yeah. In fact, I would even say that anything that happens to us is an opportunity for, one, personal work. That would be our psychological challenge. And two, spiritual practice. “May the one who snubbed me be happy. May be the one who snubbed me not be snubbed by others. May the one who snubbed me learn how to show love and kindness to all beings.” So if I go that way with what happened, I am building my own spiritual practice through being snubbed.

Ryan: Right. There’s an opportunity not only to trace back some of what this trigger might be connected to and to do our personal work around that – so that might be grieving, for instance – but then also, you’ve used this language in many of your books, saying ‘yes’ to the givens, right? Saying ‘yes’ to this reality that people won’t be loving and loyal all the time. We will face rejection. And being willing to say ‘yes’ to that, rather than resisting that reality.

David: Yes. In fact, that’s the fast track to dealing with most issues. It’s the unconditional ‘yes’ to the givens of life, one of which is that not everybody will like me, not everybody will treat me with respect. And I can speak up and say, “ouch!” but I also get it: that’s how it is here on this planet.

Ryan: You’ve identified five givens in particular, and in fact wrote an entire book on it. Can you list what those other givens are, according to your framework?

David: You’re referring to The Five Things We Cannot Change?

Ryan: That’s right.

David: And I talked about … of course, there are many givens in life. For instance, it’s a given for me sitting here in California, that there might be an earthquake within the next minute. So that’s a given. So when I chose to move here from New England, I implicitly accepted the given that I might be the victim of an earthquake. Just as when I chose to stay in New England, I implicitly acknowledged that I might suffer from hurricanes. So there are givens that go with where you live. There are givens that go with your personality. Like I’m an introvert and I get depleted if there’s too much activity and too many people around. And that’s just the given of my personality.

But the five specific givens that seem to apply to all of us, and that has to do with all relationships in life on the planet here is (1) everything changes and ends, (2) life is not always fair, (3) suffering is part of everyone’s life, (4) things don’t go according to plan all the time – in other words, we’re not in full control, and (5) people are not loyal and loving all the time. So within that is, so therefore they sometimes snub you. So if you said ‘yes’ to people are not loyal and loving all the time – some people are loyal and loving all the time to you, like one of your aunts was always loving and loyal, but that doesn’t mean she was always loving and loyal to everyone. So you’re saying ‘yes’ to those givens.

Ryan: And that removes a huge layer of suffering that often accompanies our experience around all of the unpredictable things that may come our way in life, just by being willing to ….

David: Yeah! That’s another given, that things will be unpredictable. Unpredictability is another built in given. That goes with everything changes.

Ryan: Right. Okay. I wanted to ask, because your books touch a lot on spirituality and, as you mentioned, that’s one of your primary interests. I haven’t read your book on How To Be An Adult in Faith and Spirituality. But I wondered if in that book, you talk about spiritual bypassing at all, if you’ve had any interest in that concept?

David: Yes. And by that you mean that sometimes we can get the impression that if we’re doing spiritual practices, we don’t have to work then on our psychological issues; we can just skip over them. And of course, that would never work because we’re both psychologically and spiritually oriented and we have to be attentive to both of those features of ourselves. So what I mean by being adults in our spirituality would include doing the work that takes so that we can be the healthiest specimens who are more likely to then do the practices of spirituality in an effective way.

For instance, if I’m still in the mindset of, if someone snubs me, I should snub them back, then I’m not really going to be faithful to my practice of loving kindness, in which we don’t go to retaliation. We go to wishing them goodwill instead of ill will. And in order to get to that, I would have to do some work on the part of myself that gets overly triggered and retaliatory. And I would want to trace that back to how I was brought up, how I maybe was retaliated against and how I’ve never really worked all that through.

Plus that impulse toward retaliation is an example of a conditioning that came to me from society in which we see retaliation all over the place. It’s the way the courts work. It’s just the style. And I’d have to decondition myself from that if I were really going to have a spiritual practice. But a part of the deconditioning will also entail some work on myself psychologically because now I’m on the topic of “how do I release myself from the habits that have been smuggled into me by family and society?” So it’s always going to be the combination of a new spiritual choice and clearing up whatever is still unfinished from my past.

It would be up to each of us to ask ourselves how we were conditioned and which of the conditionings we want to hold onto. That would be psychological work. So let’s use a simple example. Kindergarten, and the teacher says, “line up, stay in line, and no talking.” So we’re being conditioned to line up, stay in line, and not talk while you’re in line. And later in life, we look back at those three conditionings and we do what I call a sorting practice. So what do I want to keep as useful for my adult life and what do I want to discard because it applied in kindergarten but doesn’t apply now? So first, “line up.” That I’m going to keep. When I’m in the grocery store, when I’m at the DMV, I am going to get in line. I am not going to push myself ahead of people. I’m not going to let other people get ahead of me. I’m going to just stay in line. That was good, keep that.

Secondly, so it’s “line up, stay in line,” I’m keeping those two. But the third one, “don’t talk in line,” I am not keeping that one. I’m going to talk to the person in front of me or behind me just to pass the time of day, perfectly okay. So part of becoming an adult is you decide what to keep of the conditionings and what to let go of. So I’m going to keep the first two and let go of the third one. We want to do that with every religious belief, everything thing taught to us in school about conduct, everything society smuggled into us, and everything our peers insisted we be. So I want to go through all those and say, “which ones am I keeping and which ones am I discarding?” And then the results will be, “oh, well, this is the actual me.”

Ryan: You know, it strikes me that these conditionings are often appropriate in certain contexts but not others. And so we just have to have discernment around when it’s really not appropriate or not a fit.

David: Exactly. Yes, exactly. There may be times in life – and I’m glad you brought that up, Ryan – there may be times in life when you have to line up, stay in line and be quiet because you’re in the hospital and they want silence for some reason. So yeah, it’s not going to be totally this or that. You’re going to be matching the circumstance to the choices.

Ryan: Right. Coming back to this idea of spiritual bypassing, sometimes the habits or unresolved work that you’re referring to – say, retaliation as an example – sometimes these behaviors are unconscious or they’re just very buried within us. And so we might be telling ourselves that “actually, I have a really well-developed practice of universal love and unconditional love” and not even have an awareness that some of these more shadow elements are lurking underneath. And so we can misuse some of these practices as a way of avoiding doing the work, which can be difficult and not very glamorous.

David: Yeah. And maybe even cause us to have to have humility.

Ryan: Yeah. It doesn’t fit with the identity that we’ve crafted. Well, we’re coming close to the end of the hour and I wanted to ask: I know you have a lot of great resources on your website. Is there anything that you’d like to share with listeners in terms of resources, maybe information about the book that you’re working on right now, and just where they can learn more about you?

David: Yeah. The website is davericho.com, and there I have a listing of my books and some of the talks that I’ve given are on MP3’s that you can download. And I also have YouTube videos. And that would be a way of finding out about what I’m doing and what I’m offering. And as far as the book that I’m working on, it’ll be published by Shambhala, as are most of my other books, probably in the next year or so. So far, I’m not quite definite about the title, but it’ll be whatever the next book is, after this latest one, which is a revision of my most popular book, How to be an Adult in Relationships. I’ve revised that twenty years later. It was published in 2002 and it’ll come out again in 2022. And it’ll still be called How to be an Adult in Relationships, but it’s updated. So that’s what’s coming up.

Ryan: Great. Well David, thanks for your time and your insights. I enjoyed connecting with you.

David: Thank you, Ryan. And I really liked your questions and your seriousness about this whole project of becoming human.